Key Actions

iii. Review business relationships

The responsibility to respect human rights extends to business relationships.

Definition Business relationships

Business relationships in the UNGPs are understood to include a company’s “relationships with business partners, entities in its value chain, and any other non-State or State entity directly linked to its business operations, products or services”.

See the following:

- Commentary to UNGP 13;

- Key Concepts in UNGPs section;

- OECD Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct p26, which states: “Obtain, when appropriate and feasible, relevant information about business relationships beyond contractual relationships (e.g. sub-suppliers beyond “tier 1”)”;

- Interpretive Guide p5: business relationship is understood to include “relationships in its value chain, beyond the first tier, and minority as well as majority shareholding positions in joint ventures”;

- For a concrete example of due diligence obligations and business relationships, see the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas Gold Supplement p67, which recommends different due diligence for the three possible sources of gold and gold-bearing material.

Mapping the full range of business relationships which a commodity trading company is involved with is a key step in effective human rights due diligence consistent with the UNGPs.

The table below indicates different approaches a company can adopt to start its mapping process:

Approaches to Mapping Business Relationships

| Where to start | GEOGRAPHY | BUSINESS UNITS | ACTIVITY/SUPPLY CHAIN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rationale | Some companies find it necessary to make a geographical distinction in the mapping of business relationships because the nature of the relationships and activities is very different in each case | Some companies find it helpful to map business relationships involved in particular business units |

Commodity trading companies engage in business relationships with a broad range of actors across the supply chain in the various activities they conduct |

| Examples |

|

|

|

The box below provides an example from the sector. The mapping is based on the company’s identified activities across the supply chain: sourcing, storing, blending and delivering. For each activity, the company provides a list of what it terms “direct relationships” (where it has total control, e.g. majority-owned mines, subsidiaries and group-owned terminals) and “indirect business relationships” (where it exercises influence to various degrees).

Examples of indirect business relationships include state-owned oil refiners, marketers and producers, third-party-owned vessels leased in part or in full on a time charter or voyage charter basis and third-party-owned rail, vessels, barges, trucks and pipelines leased on a short- or long-term basis.

Example Mapping Business Relationships

One company trading energy and hard commodities included in its responsibility report a visual representation of the business relationships with which the company is involved.

| Activity | SOURCE | STORE | BLEND | DELIVER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Relationships |

Majority owned mines |

Group-owned oil storage and metals and minerals warehousing | Group-owned transport assets | |

|

Indirect Relationships |

Oil producers, refiners and marketers (state-owned or privately owned) Mining companies, smelters and marketers (state-owned or privately owned) |

Third party-owned oil storage and minerals and metals storage |

Rail network and pipeline providers (state-owned or privately owned) Oil and petroleum consumers Metals and minerals consumers |

|

|

Oil storage on third party- |

||||

Reviewing business relationships as part of due diligence as set out in the UNGPs does not automatically and fully absolve a company from liability for causing or contributing to human rights abuses. Nor does it suggest that a company has to assess the human rights performance of every entity with which it has a relationship, but it does mean assessing the risk that those entities may harm human rights when acting in connection with the company’s own operations (see Commentary to UNGP 17 and UNGPs Interpretive Guide p41).

In reviewing business relationships, traders can make their own assessment of the human rights risks associated with their suppliers. An assessment of a supplier should at least include the reviews of:

- the operating context and the potential human rights risks of the suppliers;

- the human rights policies and due diligence procedures of the suppliers;

- the publicly available information on the suppliers (media articles, civil society reports and other public documents).

The scope of the reviews will turn on the nature of the supplier’s work, the jurisdiction it operates in, as well as the nature of the business relationship that the company has with the supplier.

If trading companies lack the internal capacity to undertake such assessments, they should seek external expertise in carrying out human rights assessments of suppliers. These assessments are typically based on media articles, civil society, United Nations, governmental or other public reports (see Stage 2, iv. Draw on expertise).

Commodity trading firms sometimes use Know-Your-Customer (KYC) processes to screen customers, producers, other business partners and suppliers. The challenge is to ensure both that human rights risks are incorporated into such processes and that these steps are consistently applied to all counterparts. The box below provides an example of related due dilgence procedures in the banking sector.

Example Due Diligence Procedures Developed by a Bank

An international bank has developed a sustainability risk management process for lending that consists of five steps: risk determination, assessment, approval, monitoring and reporting.

The second step of the bank’s sustainability risk management process is the assessment of the client’s sustainability performance by means of due diligence procedures. These procedures are divided into low, medium and high risk transactions.

Due diligence of high-risk transactions consists of a thorough sustainability risk assessment to assess whether the client’s sustainability performance meets the bank’s standards for high-risk transactions (as defined in the bank’s sector-specific and cross-sectoral sustainability policies).

For high-risk transactions, due diligence involves in-depth assessment based on specific tools and methods developed for the relevant business activity or type of client.This includes assessment of the client’s capacity, commitment and track record for managing the ESE (environmental, social and ethical) risks of the transaction within the country context.

It should also look at the client’s various mitigation measures for addressing ESE impacts; including adoption by the client of good international standards and the client’s supply chain management. Furthermore, it should review, where applicable, principles related to corporate transparency, accountability and stakeholder engagement. Managing ESE impacts should be understood to include human rights and engagement with rights holders.

Global efforts relating to anti-money laundering and counterterrorism financing (AML-CTF) and politically exposed persons (PEPs) could also be relevant in this context if due diligence consistent with UNGPs is integrated into company processes.

Acquiring complete knowledge of the origin and chain of custody of commodities traded is an on-going challenge. This may be particularly the case where a long supply chain is involved or when a produced or extracted commodity is collected from multiple points, aggregated by agents and shipped. The key point is to adopt a progressive approach aimed at continuous improvement. This means that companies should be able to demonstrate a clear willingness to map human rights risks in their supply chains and increase their knowledge over time. See boxes below for illustrative examples of current trading practices, and human rights due diligence responsibilities in the context of the Incoterm rules.

Example Current Practice in the Commodity Trading Sector and Due Diligence Scenarios

High level scenarios:

1. Commodity Futures Exchanges - In cases when a seller and a buyer are matched by a commodity futures exchange, the parties involved are typically unable to undertake prior due diligence on the other party, including supply chain due diligence. Enterprises could, as part of their policy commitment to the UNGPs, individually and collectively encourage exchanges to include due diligence as part of the contract specification. Exchange deliveries are typically treated as low risk (with respect to performance), but these should be treated as higher risk for human rights due diligence.

2. Commodity Brokers - In cases when a seller and a buyer are matched by a commodity broker, that broker will typically be given a “permitted counterparties” list by its client that includes all the parties with whom that client is prepared to be matched. That list will contain only the names of companies that passed the client’s KYC processes and had credit limits put in place in respect of it. Commercially reasonable due diligence for inclusion on a permitted counterparties list can include human rights due diligence provisions.

3. Seller/Buyer Relationships - In cases when a seller and a buyer form a relationship outside a market (exchange, trading platform or network of brokers) due diligence will depend in part on what is achievable prior to the first transaction. Clauses should be included in contract terms that permit a termination of the contract in the event that a code of conduct is found to have been breached. This may allow time for a buyer to conduct more due diligence between the time of entering into the contract and the time of performance of the contract. Where the relationship is to be continued over time, it is usual to conduct more comprehensive due diligence, for example reviewing or requesting (if not publicly available) code of conduct or policies, Health, Safety, Security, Environment (HSSE) records, sustainability reports (if applicable) and additional checks on the company and its management from different systems and sources a company has access to, including resources on the ground.

4. Spot Supply Contracts - In cases when a seller and a buyer enter into a spot supply contract where the commodities are already in transit (for example on board a vessel) then it is likely that the seller will give no opportunity for due diligence other than to supply required documents (quality and quantity certificates, origin certificate, etc). Enterprises should treat these types of purchases as high-risk as it is difficult to verify the accuracy of the certificates or to conduct further due diligence. New digital technologies are being developed in an effort to address these concerns. Industry-wide action will be required to address these high-risk practices.

Incoterms and Human Rights Due Diligence

Many commodities sale and purchase contracts use the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Incoterms to describe some of the contractual rights and obligations of the buyer and the seller. Incoterms are the official rules of the ICC for the interpretation of trade terms. Contracts may incorporate Incoterms to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the level of customisation desired by the buyer and seller.

These rules typically deal with the responsibility of the buyer and the seller for delivery and payment, export and import formalities, contracts of carriage and insurance, the transfer of risk of loss or damage to the goods, the division of costs, the giving of notices, documentation, inspections of the goods, packing and markings.

Incoterms do not include specific references to human rights due diligence. The buyer and seller should agree express contractual terms with respect to human rights due diligence responsibilities regardless of the Incoterm rules they agree on.

For more information on the Incoterms rules: see https://iccwbo.org/publication/ incoterms-rules-2010/.

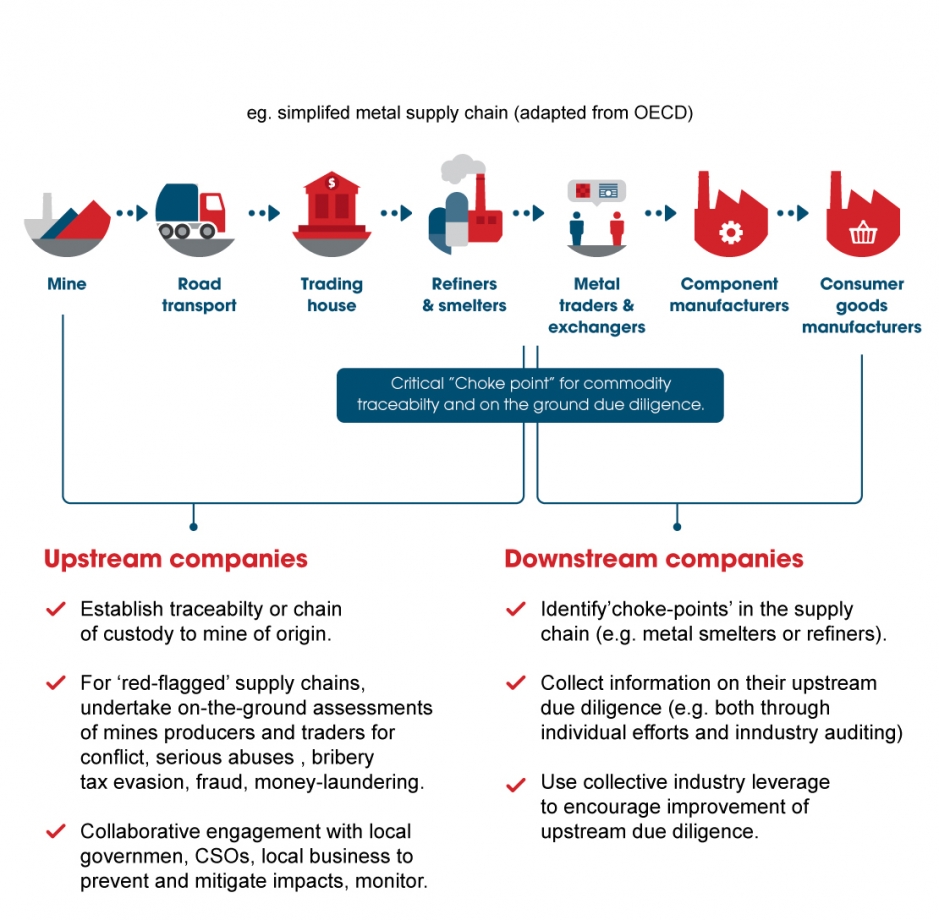

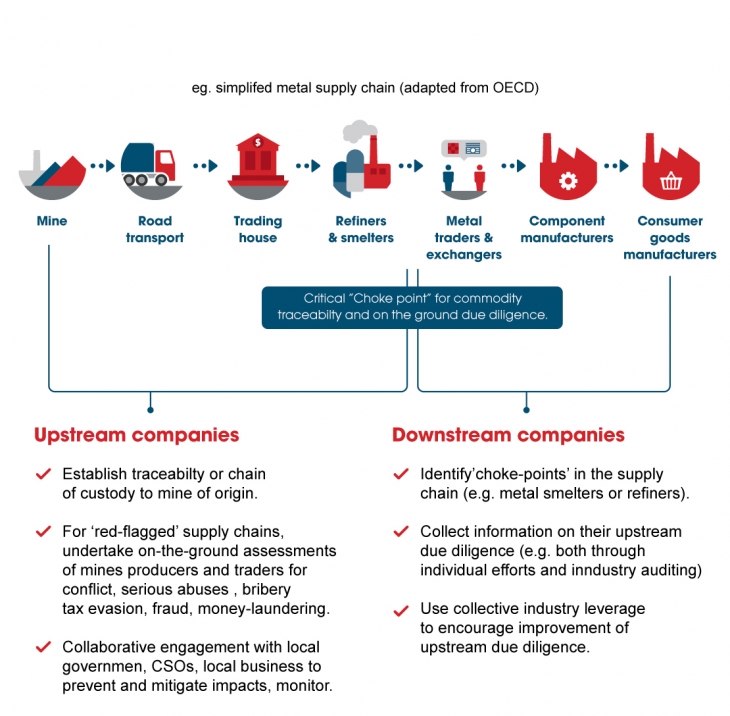

The box below outlines due diligence recommendations according to the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains from Conflict Affected and High-Risk Areas, for traders operating at different levels of the metal supply chain. This Guidance recommends a whole of the supply chain approach, meaning that implementation of due diligence takes many different forms depending on the company’s position in the supply chain. The reference to “choke point” highlights the point in the supply chain where the mineral undergoes a significant transformation and where there are relatively few actors involved. For most minerals, this would be the smelter or refiner. This Guidance calls for entities in these choke points to undergo third party audits.

Example of Simplified Metal Supply Chain and Due Diligence Recommendations

The Commentary to UNGP 17 acknowledges that carrying out due diligence on every individual relationship may be impossible in some circumstances:

UNGP 17 Commentary

…business enterprises should identify general areas where the risk of adverse human rights impacts is most significant, whether due to certain suppliers’ or clients’ operating context, the particular operations, products or services involved, or other relevant considerations, and prioritise these for human rights due diligence...

This would include, for example, minerals sourced from suppliers in an area known for human rights abuses, such as violence against vulnerable minorities, as well as discrimination of women or child labour.

Companies should map the likely structure of their supply chains to pinpoint higher risk suppliers or general areas of risk and then move onto more detailed, iterative investigations on specific stages or suppliers using a risk-based approach (OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct p17).

Small or medium-sized enterprises with a large number of business relationships may face resource constraints in carrying out effective human rights impact assessments. They should look to existing resources such as public information on risks in certain supply chains.* They should also work with their industry associations to obtain technical assistance as appropriate.